Anatomy for Contortionists 101 - Introduction

This is part of the Anatomy for Contortionists series. You can find the rest of the series at this page when the series has been released.

Understanding anatomy isn’t just for doctors and physiotherapists, it’s a powerful tool for circus artists. For contortionists in particular, knowing how the body is structured helps you train smarter, reduce injury risk, and unlock new pathways to flexibility. Let’s look at the major building blocks of the body: bones, muscles, ligaments, and tendons and why they matter when you’re folding yourself into extraordinary shapes.

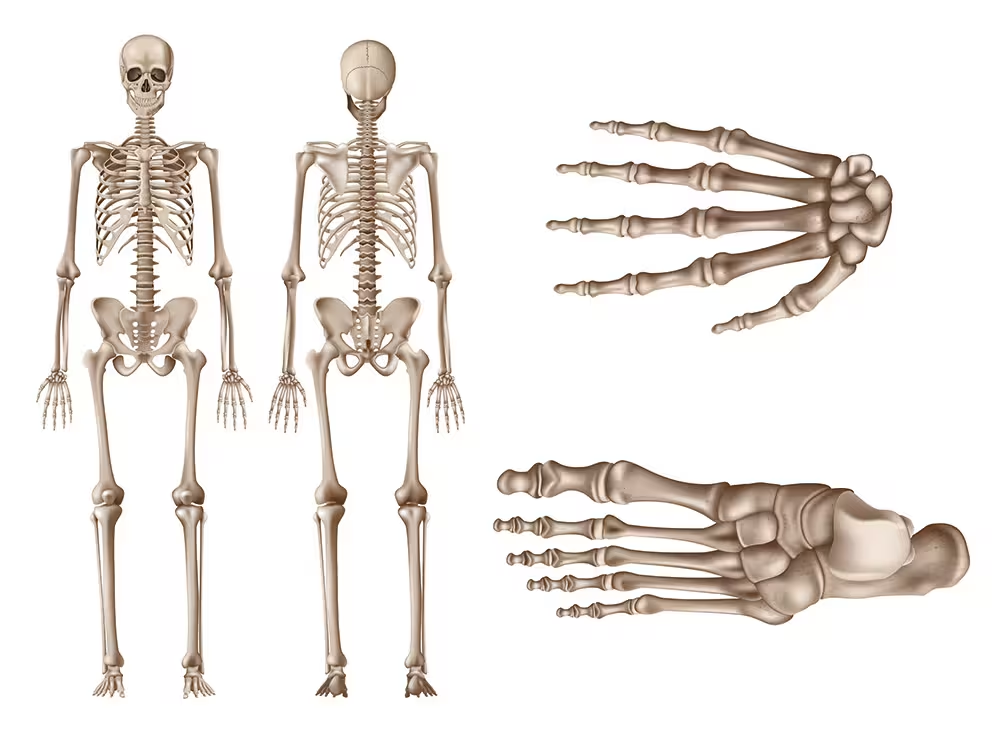

Bones: The Framework for Flexibility

Bones are the scaffolding of your body. They give structure, provide attachment points for muscles, and form the joints that allow movement.

- The spine is central to most contortion work. It’s made of 33 vertebrae, Divided into cervical (very upper back and neck), Thoracic (mid-to-upper) and the lumbar ((lower-to-mid) . Contortionists often need to learn how to mobilise **this area while keeping the lower back (lumbar spine) stable to avoid overload. The healthiest backbends are distributed across as many of these regions as possible.

- The hips and pelvis act as a base of support and are a gateway to splits, oversplits, and backbending. The hip socket is a ball-and-socket joint, naturally capable of big ranges of motion, but each person’s anatomy sets different limits. This is also where incredible rotations needed for advanced frontbending come from.

- Shoulders are another ball-and-socket joint and are crucial for bridges, needles, and arm support balances. Understanding how the shoulder blade (scapula) glides over the back of ribcage is key to safe overhead range.

Why it matters: Bone structure sets the possibility for your movement. Training expands range within safe limits, but no amount of stretching can change the shape of your bones and the depth of joints such as your hip. Recognising natural limits helps you work with your body rather than against it.

Muscles: The Movers and Controllers

Muscles are the active tissues that contract, relax, and lengthen to create movement. For contortionists, muscles are both the engine of motion and the brakes that keep you from collapsing.

- Spinal muscles: The erector spinae group extends the back, while the multifidus provides fine stability. In backbends, these muscles work hard to lift and support you.

- Hip flexors and extensors: The iliopsoas allows the hip to extend which was what you need for effective and sustainable backbending, while glutes and hamstrings extend and stabilise the hips. These muscle groups must be balanced: tight hip flexors can block splits, while weak glutes reduce control in backbends.

- Shoulder stabilisers: The rotator cuff muscles and lower trapezius control the shoulder joint, vital for safe handstands and bridges.

- Core muscles: Beyond the “six-pack,” deep muscles like the transverse abdominis act as corset-like stabilisers, helping protect your spine in deeper positions.

Why it matters: Muscles are trainable. Strengthening them provides joint support, and conditioning them for endurance allows you to hold demanding poses gracefully. Flexibility is not just about “stretching out” a muscle, but also about teaching it to control lengthened positions.

Ligaments: The Joint Limiters

Ligaments are strong bands of connective tissue that connect bone to bone, forming the stabilising walls of your joints.

- They are not designed to stretch much and in fact, overstretching ligaments can destabilise a joint permanently.

- For contortionists, ligaments are a double-edged sword: they provide essential stability, but pushing too far risks sprains or long-term joint laxity.

Why it matters: You can’t train ligaments the way you train muscles. Protect them by building strong muscular support around your joints, listening to pain signals, and progressing gradually. Ligaments take a long time to heal too, so you really want to take care of them to prevent having to take long periods of time out of training.

Tendons: The Muscle Connectors

Tendons are the cords that connect muscles to bones. When your muscle contracts, the tendon transmits that force to the skeleton, making movement possible.

- Tendons have limited elasticity. They’re strong but adapt slowly to training.

- Tendinopathy (tendon irritation) is a common circus injury, especially in the hamstrings, shoulders, and Achilles.

Why it matters: Tendons thrive on gradual, progressive load. Rushing into deep stretches without sufficient preparation puts them at risk. Gentle conditioning, eccentric strength (lengthening under tension), and consistent warm-ups help keep tendons resilient.

Putting It All Together: The Contortionist’s Anatomy in Practice

Think of your body as a performance team:

- Bones set the stage.

- Muscles do the choreography.

- Ligaments provide the safety rails.

- Tendons are the ropes connecting movement to structure.

For circus artists, success lies in respecting each element. A contortionist who understands anatomy doesn’t just bend further — they bend smarter, balancing flexibility with strength and control.

✨ Key Takeaways for Contortionists

- Train both flexibility and strength: long, controlled holds build safe range.

- Protect ligaments: avoid forcing joints past their natural capacity.

- Care for tendons with progressive loading and adequate rest.